It’s a curious irony that the people who pride themselves on developing machines capable of generating human-like responses to user-posed questions have started to sound a little bit robotic themselves recently.

Or at least they have when quizzed about the thorny issue of the use of copyrighted data in the training of their large language models.

To give you a flavour of that response, here are a couple of quotes from a recent Washington Post report into AI and copyright by two of the industry’s biggest players, OpenAI and Google.

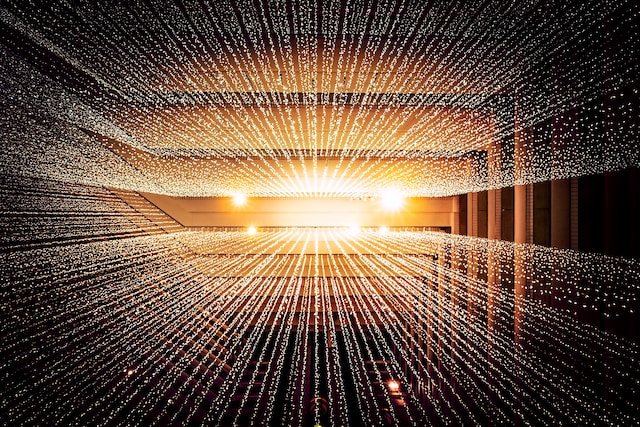

“ChatGPT is trained on licensed content, publicly available content, and content created by human AI trainers and users,” claimed OpenAI’s Niko Felix.

A Google spokesperson was more bullish but essentially trotted out the same line:

“We’ve been clear for years that we use data from public sources — like information published to the open web and public data sets…American law supports using public information to create new beneficial uses, and we look forward to refuting these baseless claims.”

Copyright holders beg to differ. In both the UK and the US, copyright infringement complaints have been filed against the likes of OpenAI, Meta, and Stability.ai, an image generator.

At the heart of these cases is an argument over how the data used to train AI’s algorithms is sourced. It’s fair to say up to now, for all their claims to the contrary, the pioneers in the field of AI have adopted a cavalier, devil-may-care attitude to copyright and author rights.

In this article, we examine the current conflict between rights holders and AI developers and take a look at how the conflict is likely to impact corporate users of AI-generated content.

AI Training Stage is Data Hungry

The training of large language models (LLMs), the technology that makes artificial intelligence intelligent, requires data.

In fact, LLMs have an insatiable appetite for data, gorging themselves on gigabytes and sometimes terabytes of digital information as they construct their statistical models and refine them.

It’s known that OpenAI’s GPT-3 LLM, which powered the first version of ChatGPT, was trained on hundreds of gigabytes of text and uses 175 parameters. The company is tight-lipped on the exact size of the training data of its latest model, GPT-4, but it is believed it uses one trillion parameters, which suggests a data size in the terabytes.

The first version of Meta’s Llama hoovered up over three terabytes of data in its pre-training stage.

Experts believe the feeding frenzy is only going to grow as AI companies seek to outperform their competitors and provide a more sophisticated human-like user experience.

A paper published in October last year by the team at Epoch AI, a research group, suggests that the data grab will mean the internet will be sucked dry of usable training data by 2026.

Transparency Issues in AI

In the early days, LLM developers were more willing to divulge where they found the vast data repositories, they used to train their systems.

Indeed, a paper by Transformer, which lit the blue touch paper on the recent generative AI boom, furnished readers with not just an overview of its sources, but a forensic breakdown of the data that was used to train its LLM, among which was over 40,000 sentences from the paywalled Wall Street Journal website.

OpenAI also obligingly explained in an early paper where it sourced much of the data to train GPT-3, and so did Meta, which provided a tabular breakdown of its data sources that fed its first LLM, Llama 1.

Today, things are a bit different.

OpenAI, Google, and Microsoft now say they decline to explain where they find the data to train their models out of fear it could be put to nefarious ends by ‘bad actors’ who might seek to replicate their work.

Meta, once so ready to reveal where it found its data, now simply says its new LLM, Llama 2, uses “a new mix of publicly available online data”.

That’s all, folks.

Pirated Content Used to Train AI

LLMs need what is termed corpora to train their models. These are vast collections of text-based documents that can be combed and analysed for statistically relevant patterns.

In the past, LLMs sourced much of their data from CommonCrawl, a compendious data set that its owners have spent over a decade scraping from every nook and cranny of the internet.

A hodge-podge of Wikipedia entries, Gutenberg public-access works, social media-type posts, archived news articles, and a spattering of mysteriously named titles make up the remainder.

One such mysterious source is the data mass OpenAI refers to as Books2 in its literature, and it’s here that some suspect that the company has been scraping copyrighted texts and infringing rights in doing so.

“We don’t know what is in that or where it comes from,” explains Andres Guadamuz, a Reader in Intellectual Property Law at the University of Sussex.

But if there is a trove of copyrighted data that’s been used to train OpenAI, it’s more than likely here, he suggests.

If, as suspected, the works in Books2 are indeed copyrighted texts, they were more than likely sources from ‘shadow libraries’, pirate websites such as Bibliotik, Library Genesis, and Z-Library that host copyrighted works and make them available free of charge.

The US comedian and author Sarah Silverman certainly thinks this is the case. She, together with writers Christopher Golden and Richard Kadrey, recently filed a complaint in a federal court against OpenAI and Meta for the breach of copyright that these “fragrantly illegal” shadow libraries had facilitated.

There is also a cache known as Books3, a vast repository of similarly pirated plain-text publications that an internet vigilante uploaded and made publicly accessible in a bid to seed low-budget startup AI projects and level the playing field with some of the big boys to train their LLMS.

A group of Danish authors recently had Books3 removed from its hosting site using a DMCA takedown, but not before the likes of Meta’s Llama, BloombergGPT, and GPT-J (not to be confused with OpenAI’s GPT) had apparently used it to train their LLMs.

AI-generated Images & Copyright

It’s a similar story in the world of generative AI image production. The likes of OpenAI’s Dall-E and Stability AI’s Stable Diffusion don’t need the plain text inputs of their language-generating cousins, but instead vast collections of images to train their models.

And by ‘vast’ we mean billions of images. According to a recent copyright case filed in a San Francisco court against Stable Diffusion, the creators of the wildly popular Stabilty.ai, the system ‘scraped’ more than five billion images from the internet to train its image algorithms.

In the UK, Getty Images filed its own complaint against Stability.ai in the High Court, alleging that they too had had their rights infringed in the training stage of the company’s AI.

Getty’s complaint asserts that over 12 million of the photos in its copyrighted online collection were used without permission or licence.

The Fair Use Defence in Copyright

AI companies have always argued that the way they use copyrighted works to train AI LLMs falls under fair use, which, in the UK, allows limited exemptions to the Copyright, Designs, and Patents Act (1988) for text and data mining (TDM) for non-commercial purposes.

Some find the claim of fair use convincing. Guadamuz is one.

“I would expect OpenAI to mount a compelling fair use defence,” he says.

“I cannot see how the possible inclusion of the books in the dataset would have an effect on the book’s market. ChatGPT at most provides a summary of the books, the same as Wikipedia. If these are indeed in the training data, their presence is negligible, and ChatGPT would work perfectly fine without them.”

The problem with this line of reasoning is that it fails to come to terms with the fact that sophisticated models with superior natural language processing capabilities require high-quality data to train them.

Computer scientists have a handy expression that neatly sums up the quandary AI developers face when training an algorithm: garbage in, garbage out (GIGO).

That is, if you pass a computer system sub-par data, don’t be surprised if it spits out sub-par answers.

AI LLM trainers are keenly aware of this tech truism and have always been concerned about the quality of their data – hence their ferreting around in copyrighted books and paywalled, high-quality newspaper archives.

The need for high-quality inputs will only grow more exigent in the future, as model makers look to refine their algorithms and outflank their competitors with ever more human-like experiences.

As the Epoch AI paper mentioned earlier makes clear:

“Our analysis indicates that the stock of high-quality language data will be exhausted soon; likely before 2026. By contrast, the stock of low-quality language data and image data will be exhausted only much later; between 2030 and 2050 (for low-quality language)”.

They go on to explain that:

“A common property of these sources is that they contain data that has passed usefulness or quality filters. For example, in the case of news, scientific articles, or open-source code projects, the usefulness filter is imposed by professional standards (like peer review).”

As such, it’s unlikely that LLMs would have made the strides they have over the past few years without the high-quality data that you find in content that is protected by copyright, licensing agreements and paywalls.

This doubtless explains why there has been a rush among some of the AI companies to secure access to content providers hosting high-quality content. OpenAI recently signed deals with AP News to use its archive of news stories and the online image database Shutterstock.

Outlook for Developers & Content Users

The UK government seeks to position the country as a hospitable place to develop AI-led technologies.

To this end, the Intellectual Policy Office (IPO), a government agency, has mooted a general exemption to data scraping for all purposes, not just research, which would give AI carte blanche when it comes to sourcing its training data.

However, the idea hasn’t sat well with the creative industries and was recently shelved in favour of a voluntary code.

How far a voluntary code can go in reigning in an industry that has hitherto shown itself to be blasé about author rights remains to be seen.

“Some stakeholders may be sceptical as to whether a non-legislative initiative such as an industry-led voluntary code of practice can strike the right balance of interests and resolve the practical and financial conundrums at issue,” says Gill Dennis at the law firm Pinsent Masons.

In the US, copyright law gives greater latitude to AI scrapers than in the UK with the proviso that the ends to which the TDM is used should be ‘transformative’.

This means that users cannot simply reproduce a copyrighted work, but if they can show they have used the work to produce something materially different – an algorithm, say – to the original they might be able to frustrate claims of copyright infringement.

“The greater freedom US law affords AI scrapers means they might prevail in some of the cases brought against them,” says James Grimmelmann, Tessler Family Professor of Digital and Information Law at Cornell Tech.

“It’s possible that some outputs from their systems will be found to have been infringed, but the early signs from the complaints and the courts are that we’re not seeing the kind of wholesale direct imitation that would make a court willing to shut down the AI projects entirely.”

However, he cautions that:

“Even if the copyright owners lose their lawsuits against the AI companies, AI users always have to consider the possibility that they could be one of the unlucky ones who cause the system to generate an infringing output.”

It’s a view shared by Barry Scannel, a lawyer specialising in AI at the Irish law firm William Fry.

“From a copyright infringement perspective, there’s a risk of damages but also injunctions preventing unauthorised use of training data, which could lead to the dismantling of your whole (enterprise) model.”

This potentially leaves them exposed to copyright infringement claims themselves, he says. As such, he urges caution at this point for anyone currently using or thinking of using generative AI.

In a recent LinkedIn post, he suggested six questions AI content users should ask themselves.

Going forward, the judges in the various AI court cases will also be asking themselves a few questions. Among them: is a piece of technology that tramples on individuals’ rights really a social good? And how do we balance technological progress with respect for intellectual property?

Indeed, the technology seems to pose more questions than it answers at the moment.

Eventually, it will be down to how humans, not robots, respond to these questions that will decide its future.

Author Profile

- Freelance Journalist & Content Creator

- Content creator and contributor, freelance journalist and writer.

Latest entries

London BusinessApril 1, 2025Top 10 Recognised London SEO & Marketing Consultants

London BusinessApril 1, 2025Top 10 Recognised London SEO & Marketing Consultants HospitalityMarch 31, 2025Top 10 London Karaoke Bars for Unique Sing-Along Experiences

HospitalityMarch 31, 2025Top 10 London Karaoke Bars for Unique Sing-Along Experiences HospitalityMarch 27, 2025Top 12 Activity Bars in London for the Ultimate Competitive Pub Game Experience

HospitalityMarch 27, 2025Top 12 Activity Bars in London for the Ultimate Competitive Pub Game Experience Companies In LondonMarch 19, 2025Top 9 Digital Marketing Agencies in London with a Track Record

Companies In LondonMarch 19, 2025Top 9 Digital Marketing Agencies in London with a Track Record